Occasionally, you hear people speaking wistfully about the days when the Champions League was precisely that: a tournament solely for domestic champions.

That was how the tournament was conducted until around the turn of the century when it was opened up to include runners-up and, subsequently, third and fourth-placed sides from the major leagues.

There were positives to this format: the high barrier to entry created a sense that you were watching a truly select group of teams.

The downside was that the quality was often highly variable. Because teams’ levels of performance can change dramatically from one season to the next, the Champions League didn’t often actually include the best team from each domestic league. In fact, given the Champions League featured merely the champions from (say) Italy or Spain, whereas the UEFA Cup may have included the second, third, fourth and fifth-placed sides, the UEFA Cup often featured the actual best team in Europe and was always more intimidating in terms of depth.

In an era of superclubs and repeat champions, that isn’t generally relevant these days, but Wednesday night’s clash between Napoli and Barcelona was a good demonstration of why the old format of the European Cup could lead to a weaker competition.

Napoli and Barcelona have both fallen away dramatically from last season. The former are now ninth in Serie A, the latter are third in La Liga. Napoli have, extraordinarily, managed to part company with three permanent managers since winning the Scudetto last year. Barcelona have already announced that Xavi will be leaving at the end of the season, although elimination from European competition might hasten that separation.

GO DEEPER

Could 2023-24 be the last chance for an outsider to win the Champions League?

Barcelona deserve credit for largely controlling the game away from home in a traditionally hostile setting. Their issue was what they did during their long spells of possession and part of the problem was an absence of genuine width. With right-back Jules Kounde tucking inside to form a back three, the width theoretically comes from the left-sided full-back and the right-winger.

But, down the left, Joao Cancelo found himself in positions to deliver the ball and either hung up unconvincing crosses with his left foot or tried to engineer a more spectacular ball with the outside of his right foot. We know Cancelo has this type of delivery in his locker, but he skewed this attempted cross for Robert Lewandowski awkwardly over the crossbar.

Down the right, Lamine Yamal was bright in the opening stages. At the age of 16, it feels almost churlish to criticise him in terms of decision-making or not having an all-round game, but in this situation, when receiving a pass from Ilkay Gundogan, a right-footed player would surely have gone on the outside of the defender and crossed for an unmarked Lewandowski.

Instead, Yamal drove inside onto his favoured left foot and shot with the defender perfectly placed to make a block. When you see situations like this, you can understand why Lewandowski is supposedly unhappy Barcelona do not use an extra winger.

Maybe the most telling thing about Barcelona’s current state is that they’ve taken to playing Andreas Christensen in midfield. Christensen is a fine footballer who thrives when used as the spare man at the back, was excellent in midfield during Denmark’s Euro 2020 victory over Wales, and played well there at the weekend, a 2-1 win at Celta Vigo. With Barcelona’s current defensive record, there’s merit to using a converted defender in midfield.

But this is Barcelona, the club who have a reputation for producing a string of ball-playing deep midfielders, so it’s quite depressing to see Christensen in that deep midfield role, receiving a pass from defence under no pressure, taking a touch so heavy that it invites two opponents to make a challenge, then compensating for his error by haring after the ball and clattering into an opponent almost for the sake of it.

Napoli, as expected, were even worse. This was Francesco Calzona’s first game in charge and he inevitably struggled to send out a cohesive side. “Considering our tactical problems, we struggled at the start, but I can understand there is some confusion after only one and a half days of working together,” he said afterwards.

The general approach appeared to be reverting to something more like the way Napoli played under Luciano Spalletti — building up play from the back and using a four-man defence — after a period of playing a more cautious brand of football and, on occasion, a three-man defence under Walter Mazzarri.

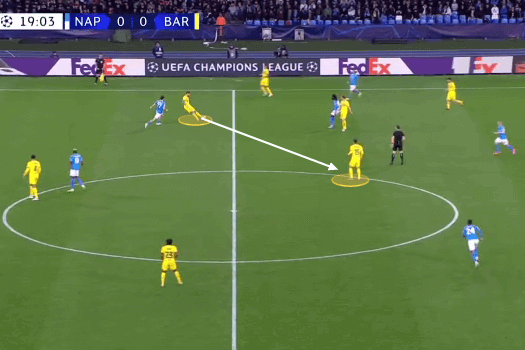

But Napoli looked like they’d forgotten how to play that way. Here, Mathias Olivera dribbles past Lamal and into an interesting position, in central midfield, and has the option of switching play to Giovanni Di Lorenzo. But then he seemed caught between two simple passes, to either Andre-Frank Zambo Anguissa or centre-back Amir Rrahmani. His pass bounced off Anguissa, ran loose, and Rrahmani had to charge into midfield to make a tackle.

There was also little cohesion up front, with Victor Osimhen back in the side but constantly timing his runs poorly and getting caught offside, before complaining to his team-mates that the ball wasn’t coming fast enough.

Here are two very different incidents, but in both of them, the Nigerian was quite clearly offside when he probably didn’t need to be.

What both sides still offer is individual quality. Lewandowski’s opener was a trademark goal, getting the ball out of his feet quickly and firing an early shot which surprised the goalkeeper. Osimhen’s equaliser was also a well-taken goal, although it was notable that he was immediately substituted afterwards, a sign he’s not yet up to full fitness. Napoli arguably played better in the closing stages after the introduction of various substitutes.

Barcelona must now be considered the favourites to progress, although there’s a sense that either of these sides might do well to be eliminated at this stage after battling well against a fellow league champion. The alternative is progression to the next round, of course, but potentially then elimination after a heavy defeat. You’d fear for either of these sides against Manchester City, for example.

Realistically, there’s a good chance the winner of this tie will be the weakest side in the quarter-finals, which speaks volumes about the regression of last season’s champions from, according to UEFA’s coefficients, the second and third-strongest leagues in Europe.